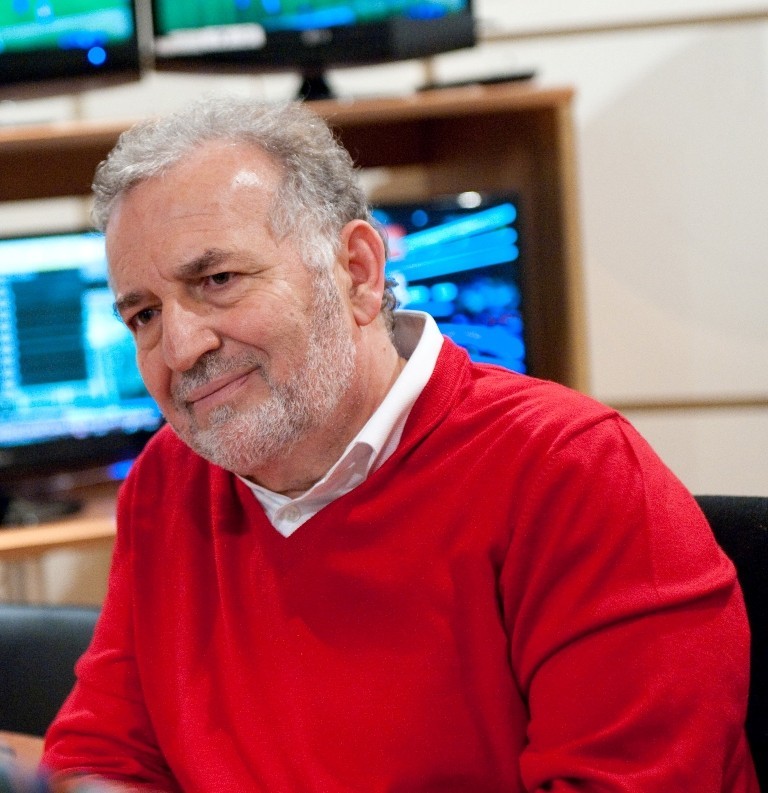

Charalambos Nikopoulos

The collective fantasy of lasting and carefree happiness leads people to be unprepared for the onset of a serious illness such as cancer

Psychiatrist - psychotherapist and notable author Dimitris Karagiannis answers questions of life and death, standing boldly, courageously and honestly in front of the threat of the disease, and showing us deeply philosophical ways to approach the issue.

What are the first feelings of a person who learns that he is ill? And how do these feelings shape up as treatment progresses?

When people become aware of the existence of a serious disease, along with the pain, they excruciatingly experience the existential questions that come to overturn their course until then. The difficult situations of the past are like games, when a tumor, a threatening disease appears. People when hospitalized for serious oncological diseases are in a state of failure, discomfort, frustration, pain and tension. They experience the utmost anxiety for their lives. Their lives are turned upside down and their meaning is questioned. They wonder if they have ever truly loved or if they can truly love. They are faced with demanding and difficult living conditions in which they have to learn to live with the uncertainty of the final outcome. At the same time, their philosophy of life, values, plans, dreams, expectations and hopes are threatened. They are faced with major revisions and radical changes that affect the status and structure of the family. The past seems distant, disconnected from the present, idealized or forgotten, while the threatening future is pushed aside as they avoid setting long-term goals.

Do they feel a kind of frustration? And how do you explain that they sometimes express a refusal to accept reality?

They realize that any investments they made in achievements or goals turned out to be worthless stocks that led them to total poverty. Then they are uncovered by what covers them and are left unprotected against the absurdity of existence, when it lacks a meaning that goes beyond individuality. They seek to deposit their pains, fears and anxieties and feel driven to a dead end, while at other times in a desperate defense they pretend that nothing bad is happening and that everything will pass. At one extreme lies a rebellious attitude where the refusal to acknowledge pain and evil in life leads to the search for some scapegoat.

At the other extreme, there is a fatalistic attitude where pain is a given and insurmountable and all that remains is to manage it so that it has the least possible impact on life.

What is the role of their own people in managing this difficult situation?

Trying to solve with the help of their own people, partners, parents or friends, often leads to a greater degree of involvement as, by asking the question dead ends, the answers they receive are correspondingly dead ends, since their own people also experience corresponding painful uncertainties. It is then that relatives and friends, trying to comfort, risk pretending and seeking to cover up situations, inadvertently creating greater loneliness. Hope is genuine when it coexists with truth. When it leads to evasion, denial or concealment of the truth, it is an illusion and corresponds to the weak.

How much truth and how much comfort can each patient accept? Is there a golden rule?

The advice: "Don't be sad» it is deeply hopeless. Refusal to accept sorrow means that the touch of sorrow at some point will be overwhelmingly destructive. Indeed, it is a solution, when you have not shared the sorrows of others. It is cathartic if you are surrounded by a scene of bliss and euphoria. It is unbearable if you have managed to convince yourself that there is some way that if you apply it you will be saved from the test of existence. The command "Don't worry" is not really aimed at the one to whom it is addressed, but at the one who expresses it. If we translate it, we will hear: "Don't be sad and make sure you have a good time, because I can't stand unpleasant situations." Therefore take care not to be sad, even if something very unpleasant has happened to you, because then you are making it difficult for me too and I can't stand it.

How does a doctor feel when he has to announce something unpleasant and how does the suffering of his patients affect him?

For a psychiatrist like me, announcing a child's serious disorder to his parents is a daily ordeal. No one wants to be the first to announce it. In general, the decision to endure to refer to the truth of the facts and to avoid giving false hopes, which eventually become carriers of despair, is extremely difficult, complex, painful. However, this demanding accompaniment to the pain of others becomes an occasion for substantial existential searches, which do not concern only some people facing difficult times, but are universal. For example, you might hear a young person learning they have cancer never ask "why me?" because he finds it unethical, and you to trivialize your personal life for something that is reversible or just comes with some financial price? People who would have the ultimate alibi for disappointment, such as people with serious terminal illnesses or parents of children with severe mental retardation, give the Resurrection message that deep joy is not given, but won in the struggle of pain.

How does the psychotherapeutic approach you serve deal with the issue?

The existential approach does not doubt the painful consequences that any life-threatening illness can have on the mental health of the sufferer. However, it does not accept the unilateral recording of the psychopathological consequences, without the corresponding recording of the positive forces that may emerge from the therapeutic treatment of negative experiences. It is a healing attitude that does not blame, but does not gloss over the signs of the threat of illness, it states that pain is always unavoidable in our lives and no one can pretend to seek it. But its appearance can set in motion underground powers of man that will enable him not only to experience the transcendence of pain, but to acquire elements of wisdom.

And for those who succeed and overcome cancer? What effects does this have on their psyche? Are they becoming better people?

The processed experience of pain creates antibodies for the rest of life. It makes you more humble as you recognize your limits. It allows you to be more sensitive to other people's problems without insulting them with your pity. It teaches you to distinguish what is important and what is secondary. It forces you to answer existential questions seriously. I feel grateful for all those people who allowed me to be close to them in their genuine pain, as through their tears they could be so human. These experiences make me feel confident when I refer to the fact that today there are too many people who honor their existence. People who until the end of their lives adorn modern society with their inner quality.